In Memory of Rabbi Adin Even Israel Steinsaltz

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz was one of the most prolific and preeminent rabbis of our generation. Born to a secular family in Jerusalem in 1937 to a father who was an ardent communist, young Adin, an only child, had read every socialist and communist publication he could get his hands on by the age of 14. On the other hand, his father also told his sensitive son, “A Jew cannot be uneducated or ignorant of the Torah” and agreed for Adin to spend time studying Jewish texts.

Meeting an old Chabad Hasid in Jerusalem’s Meah She’arim neighborhood, the brilliant young boy began to study, poring over Talmudic and Hasidic texts and then returning home to delve into books on chemistry, physics, literature, philosophy, sculpture, and anything else he could get his hands on. He was curious, interested in everything. By his 24th birthday, the young R. Steinsaltz was giving classes in Jewish thought with quite a few university professors in the audience, including Israel’s President Zalman Shazar.

Years later, R. Steinsaltz reflected, “these people, several of whom could have been my grandparents, didn’t want to hear my little voice. They wanted to hear the powerful, meaningful voice of Judaism, that voice that comes from Mount Sinai. The sound of Sinai has been wandering and winding its way through the Jewish people for generations. At the moment that I am teaching, it happens to be flowing through me. So, according to this count, I am now 3,000 years old, bringing the words of Mount Sinai to these famous professors…”

Indeed, by the time R. Steinsaltz succumbed to pneumonia at 83 a little over a month ago in Jerusalem, he had performed a feat that no one since the medieval French Rabbi and commentator Shlomo Itzchaki (Rashi) had accomplished in the 11th century. Working 17-hour days, R. Steinsaltz translated and commented on all 63 volumes of the Babylonian Talmud, which stretches over 2,700 double-sided folio leafs, unlocking the closed pages of Jewish law, ethics, folklore, history, and tradition to the modern reader in Hebrew—with translations published in English, Russian, French, Spanish, Italian, and even Chinese. His published works also include more than 60 books, with commentary on the Torah, Mishna, Maimonides, biblical and Talmudic personalities, alongside his original commentary on the Tanya, books on Hasidic philosophy and other areas of Jewish thought, and even zoology.

|

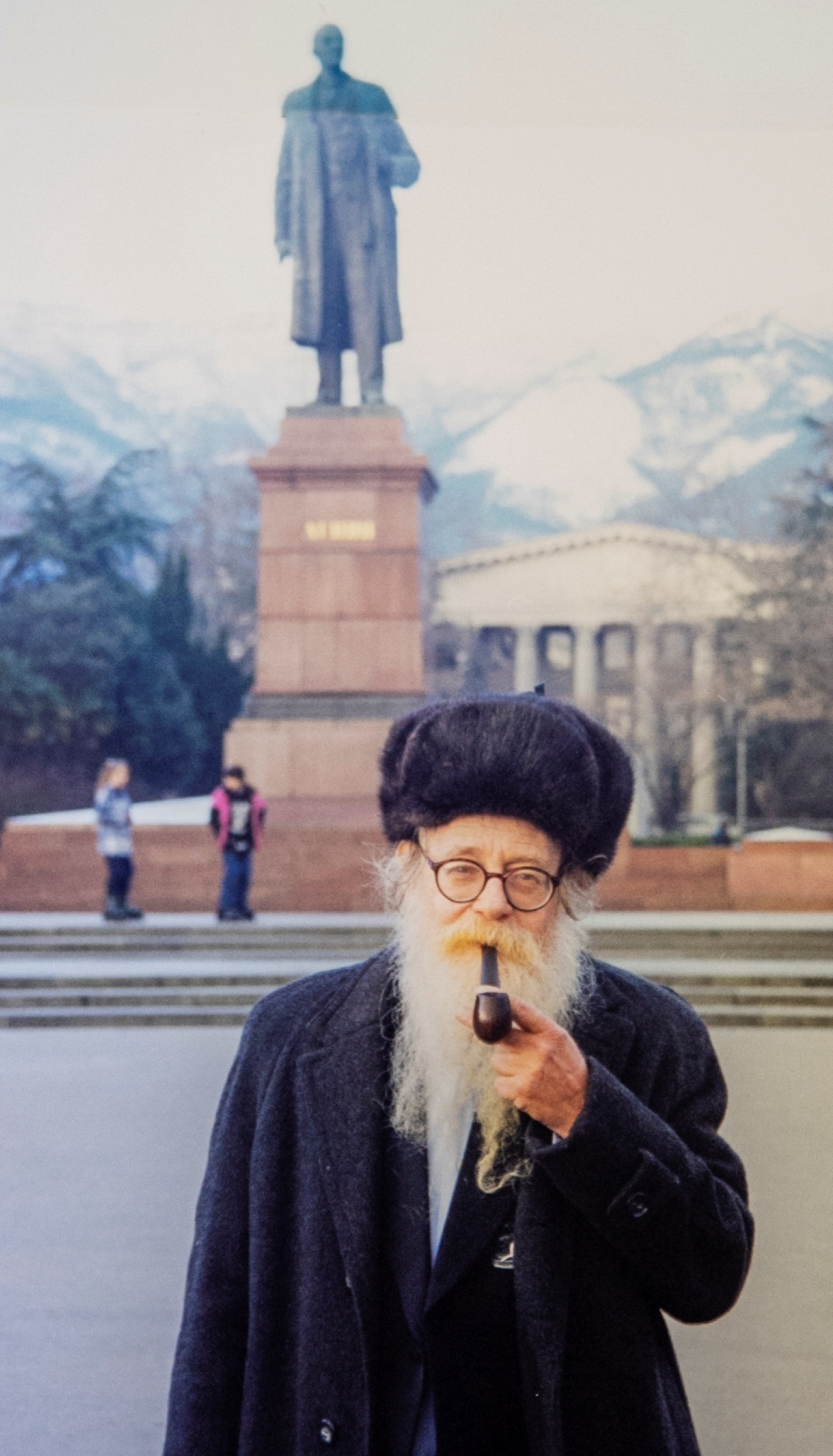

on the Yalta embankment |

What I will miss most, however, is R. Steinsaltz the person. When I began working for him in Russia in the mid-1990s, he compared the Jews of the former Soviet Union to a tree that seemed dead above ground but whose roots were alive and could be watered and nurtured back to health. I visited countless communities across the 11 time zones of what was once the Soviet Union and in each place I witnessed how he toiled to nurse the roots back to health.

How did this Israeli-born Talmudic scholar, who was at that point still far from finishing his life project of translating the Talmud and making it accessible to the modern reader, come to be involved in Russia? The true background to this part of his life, and his involvement in the astonishing renaissance of Soviet Jewry as the Iron Curtain was finally coming down, is little known and has been underreported.

In April 1988, R. Steinsaltz skipped the Israel Prize ceremony, which was being awarded to him that year, to deliver a lecture at the Global Forum at Oxford University. The forum, created to mirror the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum in Davos, brought together political, social, academic, and religious leaders for a five-day retreat to address and try to resolve global issues.

The forum in Oxford took place at a time when the liberal members of the Soviet leadership were trying to strengthen contact with the West. In addition to Mother Teresa of Kolkata, the Dalai Lama, the archbishop of Canterbury, World Muslim Congress head Dr. Inamullah Khan, astrophysicist Carl Sagan, scientist James Lovelock, various American congressmen, and other well-known academics, influential members of the Soviet Politburo actively participated in the forum.

R. Steinsaltz spoke last. Although a recording of his speech has not been preserved, his presentation apparently made an impression on professor Evgeny Velikhov, a Soviet nuclear physicist and the deputy chairman of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. In addition to his academic standing, Velikhov was a close confidante of Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev and a consultant to the closely guarded inner circle of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet. On a walk through Oxford’s winding cobblestone alleys following his talk, Velikhov spoke to the renowned Talmudic scholar about the changes taking place in the Soviet Union and his hope that these changes would lead to a greater freedom and openness for Soviet academics.

In turn, Steinsaltz described Russia’s historical role, despite pogroms and severe suppressions, as the heartland of Jewish culture for more than three centuries. In that context, R. Steinsaltz suggested that the Soviet Union, a vast country facing economic disaster and with a desire for closer ties to the West, could benefit from the establishment of a center for religious study where students and researchers can pursue their interests in a free academic atmosphere. Steinsaltz proposed that such an initiative could be a part of the Soviet Academy of Sciences and hinted that he would be ready to serve as the director of a newly established Jewish academy where students could study Talmud, Jewish law, and the Hebrew language without fear.

Years later, Velikhov, who is not Jewish, recalled that he found R. Steinsaltz brilliant, honest, a man of integrity, and different than other religious leaders in that he wanted to create and not take anything from the Soviet Union. Taken with Steinsaltz’s idea, he invited the rabbi to travel to Moscow to deliver a lecture at the Soviet Academy of Sciences and meet with influential Soviet academics and government representatives, even though the Soviet Union still did not have diplomatic relations with Israel. Should Steinsaltz and his presentation be well received, Velikhov committed to support the idea of the center’s creation.

An approval by Gorbachev

In October 1988, R. Steinsaltz delivered a lecture to a select group of leading Soviet scientists where he spoke about the universal values of Judaism and their importance for the world of today. Velikhov, as well as the famous physicist and head of the prestigious Space Research Institute Roald Sagdeev, were both in the audience. Following meetings with key Soviet figures, Velikhov urged Mikhail Gorbachev to facilitate the opening of R. Steinsaltz’s Center for Jewish Study and Research as part of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. Gorbachev agreed.

With Gorbachev’s approval in hand, R. Steinsaltz opened the first official center for Jewish studies in the Soviet Union in more than a half-century. In addition to the underground teachers of Hebrew and Judaism who emerged from hiding, Velikhov’s powerful influence also allowed for educators from Israel, Europe, and the United States to teach at the new center in Moscow. As part of the agreement, R. Steinsaltz also received permission to microfiche Jewish books and manuscripts housed in Leningrad and to make them available to libraries in Israel and the West. Importantly, this government-sanctioned institution opened the gates for other Jewish institutions, schools, and yeshivot to open with government approval in the former Soviet Union.

Initially housed in a few small rooms in the Academy of Sciences, the new center was soon in need of far larger premises. The housing issue was resolved when Velikhov received approval to transfer the dacha, or country house, of Moscow Mayor Gavriil Popov to R. Steinsaltz for his new center. It was in one of the rooms of the large country house, with high ceilings and heavy drapes covering the double paned and heavily painted large windows, thick rugs and Soviet-style furnishings, that I first met R. Steinsaltz.

The truth is that I had first “met” him years earlier through his books. I don’t remember whether it was during high school or my first years in college when I came across The Thirteen Petalled Rose. The book struck me with its originality, depth, and clarity, and somehow the Jewish mystical view of reality became far more my own.

Having moved to Israel on a break from graduate school to study at Yeshivat Hamivtar with Rabbis Brovender and Riskin in Efrat, I continued to read his books. I knew he lived in Jerusalem, but I was far too intimidated by his brilliance—and the fear that he would ask me a question that I would be unable to answer—to consider a personal meeting. A quote from his work that would later become part of the introduction to his book on the weekly Torah portions (Talks on the Parasha) particularly struck me:

In early versions of the Talmud, the following inscription was added to the title page of each tractate: “‘Everything that is written here about non-Jews refers not to contemporary non-Jews but to the non-Jews who lived in past times.’“ [So the Jews would not be persecuted for studying these books.]

In the title page of Torah literature published today, similar disclaimers still appear—but they are invisible. They read, “Everything that is written here about Jews refers not to contemporary Jews but Jews who lived in past times.” For this reason, it is a relatively simple task to sit and study Bible, Talmud, or musar literature, since the information contained in these works does not apply to us or to our generation but to other people and other times.

This notion—that the book is addressing someone else, that it is practically irrelevant for us—must be erased from those invisible inscriptions. Whether it is the Bible, a musar text, or the Talmud, the inscription should be the exact converse: “Everything that is written here refers not to Jews who lived in past times but to contemporary Jews.” The contents of this book are speaking specifically to and about you—it was all written for you and obligates you. Before anything else, this relates to you.”

Although I spent my formative years in New York, I was born in Russia and able to speak the language. In the early 1990s the Memorial Foundation for Jewish Culture, and others, asked me to travel to the Soviet Union to teach at various programs and seminars. Though my parents were very anxious, and warned me that it was far too dangerous, I loved these visits. I found teaching people who were new to Jewish study quite exhilarating and loved walking the streets of Moscow, Leningrad, Kyiv, and dozens of other Soviet cities and towns.

I won’t bite your head off

In 1995, R. Chaim Brovender was invited to teach at the Steinsaltz yeshiva and spent lengthy stretches of the year in Moscow. Returning to Israel in late March, R. Brovender asked me whether I would consider spending Passover at R. Steinsaltz’s center in Moscow to teach and lead the Seders. My first question—and condition—was that if R. Steinsaltz would be there, I would not go. I was far more intimidated by him than the drably dressed, baton-wielding Soviet police officers. Assured that he would not be present, I agreed.

Throughout the week of Passover, hundreds of Russian Jews took part in the Passover program. The country house had a beautiful winter garden that served as a backdrop to the large dining room that was used as a synagogue, classroom, and, when all furnishings were removed, for Shabbat meals and the Pesach Seders. Jewish books, mostly in Hebrew, lined the walls, with a large handwritten sign, in shaky Hebrew, with words from Pirkei Avot (6:2) boldly painted in red that proclaimed at the entrance to the room: אין לך בן חורין אלא מי שעוסק בתורה – “The only free man is one who occupies himself with the study of Torah.”

The experience was incredible. The classes I prepared proved totally insufficient to satisfy the students’ curiosity. They asked penetrating questions, challenged rabbinical positions, quoted Russian literature and poetry in analyzing texts. While a few came for the meals to socialize and inquire about the situation in Israel and the States, most of the students wanted to study and to study in depth. Initially, there was a meekness about them, an air of distrust, at times even anxiety and fear, but once comfortable they tried to unpack each text that we were studying with great eagerness to understand. I was embarrassed by how much I did not know. They made me work hard and I relished every minute.

Following an intense two weeks, I was ready to leave. As I was packing, I was told that I had a call. There were only a few telephones in the whole building, and they were the old kind with rotary dials that made it almost impossible to get a number right on the first or second try. I had not received a call my whole time there. The administrator of the center was on the line, calling from an office in the city, and asking me to stay a few more days. The reception was terrible and the only words that I could understand were that a rabbi was coming to visit the center and they wanted me there. For some reason, it never occurred to me that the rabbi he was referring to was R. Steinsaltz.

A tall wooden fence fully surrounded the grounds of the center—it was rumored that Yasser Arafat and other leaders had stayed here when it was the Moscow mayor’s summer residence and the grounds were fully concealed from the outside by a tall, green, peeling fence. For cars to drive in, the guard, an old, heavyset man who wore a winter coat even in the summer months, would need to open the heavy metal lock and swing open two large gates. From the large window, I saw the guard struggling with the lock, eventually succeeding to let in a black Lada that had smoke coming out both from its hood as well as from inside the window of the front passenger seat. The car drove up to the main entrance and a small elderly man with a yellow beard emerged, his right hand holding a pipe, the other holding on to his hat. A fear ran through me. It was Rabbi Steinsaltz.

They told me that he wanted to meet me the next day. I spent the entire night preparing for the meeting. I nervously reviewed the daf that we had learned before I left for Russia, tried to remember the Rashis, the disagreement of Tosefot, the opinions of the Rishonim. I could barely focus on the page. I had to prepare for a class that I was giving on the following morning but nothing seemed to stick. I knew that I was not prepared to meet the rabbi.

The following afternoon, and without much fanfare, he came into my room, looked at me, smiled, and said, “Don’t worry, I won’t bite your head off.” I was not so sure. “Tell me a little about yourself,” he asked. The smoke of his pipe put me somewhat at ease, but I could barely get any words out. I started to tell him a bit about myself and then he took over the conversation. he explained the way in which he saw the current state of Russian Jewry, using examples from the French Revolution, quoting Aristotle, interspersing his thoughts with a joke here and there. When he stopped to take a sip from his coffee (I would learn that he drank it very strong with six spoons of sugar) he was particularly interested in my relationship with my teachers and people who I learned from. I related my experience in teaching during Passover and asked him what he considered to be successful ingredients for a good teacher.

|

Rabbi Steinsaltz teaching a class in Sevastopol, Late 1990's |

I don’t remember all of what he said—we spoke for more than three hours—but I do remember the main point of his response: “You see,” he observed, “of course one has to have a mastery of the subject. One has to love to teach. And one has to have passion. Without passion, very little will succeed.” He looked up at me with his playful, somewhat mischievous eyes, and added, “It is also good to have a Russian sense of humor.”

“What is a Russian sense of humor?” I asked. His reply: “Not the silly, empty American type. The Russian kind that is built on knowledge and wit.” And he then spoke about the great Russian-born Hebrew poet Avraham Shlonsky and the Russians that came to Israel before the establishment of the state.

I mentioned how insufficient I felt my knowledge was. He looked at me inquisitively, trying to figure out if I was genuine. “That’s good,” he said, “keep on learning and study seriously. But don’t take yourself too seriously…”

A few days after returning to Efrat, I was asked to meet R. Steinsaltz in his Jerusalem office. Looking up at me from his papers, he said, “You see, all I have is people. Without people, nothing can happen. I don’t know how much you can do. I don’t know how much I can do. But we must try. With passion…”

For the next five years, while continuing my studies in yeshiva, I traveled to Russia to teach and lead seminars for R. Steinsaltz. When more funding became available, he suggested that I head a new initiative in far-flung communities in Siberia where there were Jews but few possibilities for Jewish education. We created a Jewish studies program with participants receiving newly written materials on different areas of Jewish thought buttressed by four annual seminars in which hundreds of program participants came together for a week of study that included Shabbat and a separate program for children.

It was an incredible time, from which I treasure many memories and gems that I learned from R. Steinsaltz. He also introduced me to many special people, including the legendary Ralph Goldman z”l, executive vice president of the JDC who became a mentor and dear friend; religious leaders, including those of other faiths; and influential academics, philanthropists and political leaders. I was always taken with his unique ability to connect with others, many of whom held different worldviews, and do so in a way that his original thoughts, positions, and convictions were relayed with lasting influence.

Don't forget the passion

On the lid of the piano in our Jerusalem home there is a photo taken from a seminar that took place near Moscow in the late 1990s. R. Steinsaltz and I are dancing in a circle of others—and he is pushing me to move forward, to dance faster. In many ways, that is the way that I remember him—always encouraging me and those around him to accomplish more, never to be satisfied with what was done yesterday.

In Russia, he was accorded the title Duchovny Ravin (Spiritual Rabbi), a historic Russian title indicating that he was the spiritual mentor of Russian Jewry. For thousands of Russian Jews, he is and will always remain the spiritual rabbi of post-Soviet Jewry.

When my wife, Jenny, and I married in Jerusalem in 1997, he read the ketubah and gave us his book In the Beginning: Discourses in Chassidic Thought as a gift. He inscribed the book with the following words, “All beginnings are hard—please make sure to take care. And live your lives filled with passion.”

At my daughter’s wedding in August 2018, despite a debilitating stroke two years earlier that caused him to speak with great difficulty, he slowly walked up to the chuppah to recite one of the sheva berakhot. During the dancing, he surprised us by asking people to help him up so that he could join the dance. When he clasped hands with the hatan and me, he again pushed me to dance faster, with more energy.

When I was being interviewed for a position at the Avi Chai Foundation in 2000, I met the rabbi to seek his advice. Once again, we met in that little office in central Jerusalem. It was after midnight. I told him about the possibility and asked him what he thought. “If a person is lucky, he gets a chance in life to fly. You may have learned the mechanics of flying, but you haven’t taken off yet”—he then proceeded to explain how birds fly, using names and examples that I had not heard of. Once he finished the lesson in zoology, he ended with, “This offer may give you a chance to really fly. Just don’t forget the passion …”

He proceeded to explain that people may do a mitzvah here and there, igniting points of light that take place sporadically, haphazardly. “To really fly,” he said, “you have to do far more than individual mitzvot. You have to create movement, motion in which there are not individual dots but action that can cause change.”

Throughout my years of working for him, it was clear that R. Steinsaltz could not abide phoniness or foolishness, and he had no patience for people who showed off their knowledge or tried to impress. He was a sort of rabbinic Peter Pan, adventurous, free-spirited, mischievous—the young boy who can fly anywhere and never grows up. He was the leader of his own Neverland, writing about demons, angels, fairies, wizards, and, occasionally, ordinary children from the world beyond. He especially loved interacting with children and often had groups of young students around him.

|

Rabbi Steinsaltz Identifying Ancient Greek Jewish Stones, Sevastopol Museum, Late 1990's |

Though he considered himself a Hasid, he was loath to have Hasidim, followers, and he rebuffed any sycophantic admirers who wanted to be his students. He urged his students to be the best that they could be in whatever fields that they chose, and not to be his copycats, lackeys, or groupies.

He remained outside of the box, detesting labels or specific identities. He paid a price for being unique. He had many critics who wanted to censure, shun, or excommunicate him. This frail, soft-spoken man had the power of a giant, sharing his knowledge and unique ideas with simple people and Supreme Court justices alike.

He had no desire to be befriended by the powerful; his goal was to teach Jewish knowledge, which he insisted had the unique power to transform the world.

Despite an acerbic personality—he could be critical, with biting comments aimed at those around him who tried to speak about things that they did not understand—R. Steinsaltz believed in people, admiring those who could withstand the difficulty of life and make change. He didn’t suffer fools gladly, challenging his interlocutors to make change, first in themselves and then in all those around them.

Last month, as R. Steinsaltz lay in the intensive care unit of Sha’arei Tzedek, his granddaughter Racheli was hospitalized one floor above in the same hospital. Racheli was nine months pregnant and had come to the hospital feeling labor pangs. “Adin is waiting for Racheli to give birth,” his wife whispered to me.

Indeed, the very same day that R. Steinsaltz’s first great-grandson entered the world, he returned his soul to his Creator.

And yet, he had not finished his work on earth. His wife, Chaya Sarah Azimov (a distant relative of the writer Isaac Asimov) and the scion of an illustrious Chabad family, once told me that after a private meeting with the Lubavitcher Rebbe, the Rebbe told her that everything that R. Steinsaltz writes should be published and disseminated widely—even his small remarks and observations should appear in print.

One night at the shiva, together with a few of his grandchildren, I walked into his small Jerusalem office. I caught a whiff of his pipe and imagined him sitting behind the small desk, that unique smile, those searching eyes.

The closet was filled with boxes, one stacked atop the other, labeled with the words, “unfinished manuscripts/unfinished projects.”

His son Meni took a break from sitting shiva to show me the beginning of an interactive digital website that is being created from all of R. Steinsaltz’s commentary and writing. In this way, his unique voice will continue to impact the world.

Now, as Rabbi Steinsaltz would say, it is time for the sound of Sinai to wander and wind its way through us.

Also at Beit Avi Chai