Novogeorgievsk, a small town in the south of Ukraine, where Pinchas Litvinovsky, then Piotr Vladimirovich Litvinovsky, was born in 1894, is no longer on modern maps. This was a military town that housed a huge fortress built by the Poles in 1615. It was eventually abandoned but then once again revived by the Russians as a hoped-for protection against the German forces during WWI. That plan failed miserably. In the 1960s, during the construction of the hydroelectric station, the city was flooded by the Kremenchug water reservoir and disappeared forever into the depth of the Dnipro River.

Though within the Pale of Settlement, this provincial town had relatively few Jews—according to the 1897 census, out of 11,594 inhabitants only 1,455 were Jews. Yet in addition to a beautiful church with a bell tower, there were ancient synagogues, a Jewish cemetery with tombstones adorned with Jewish and folklore symbols, and Talmud Torahs.

Son of Ze’ev, a merchant, and his wife Chava, Pini—the diminutive by which Litvinovsky was known in his younger years—studied at cheder, spending his youth in his hometown with its cherry and apple orchards, floodplain meadows, a small market that broke into the local quotidian existence once a week, and bright starry Ukrainian nights, like the ones in the stories of Gogol.

However, life for Jews was far from tranquil. The period around Russia’s First Revolution in 1905 caused mass political and social unrest and extensive violence against Jews. By December 1905, news reached even the faraway New York Times that reported Jews being massacred in the Kherson districts that the town of Novogeorgievsk was part of. Though his family did not flee, young Pini and his parents and siblings, like Jews in all the Pale of Settlement, must have been constantly under threat.

New ideas and directions

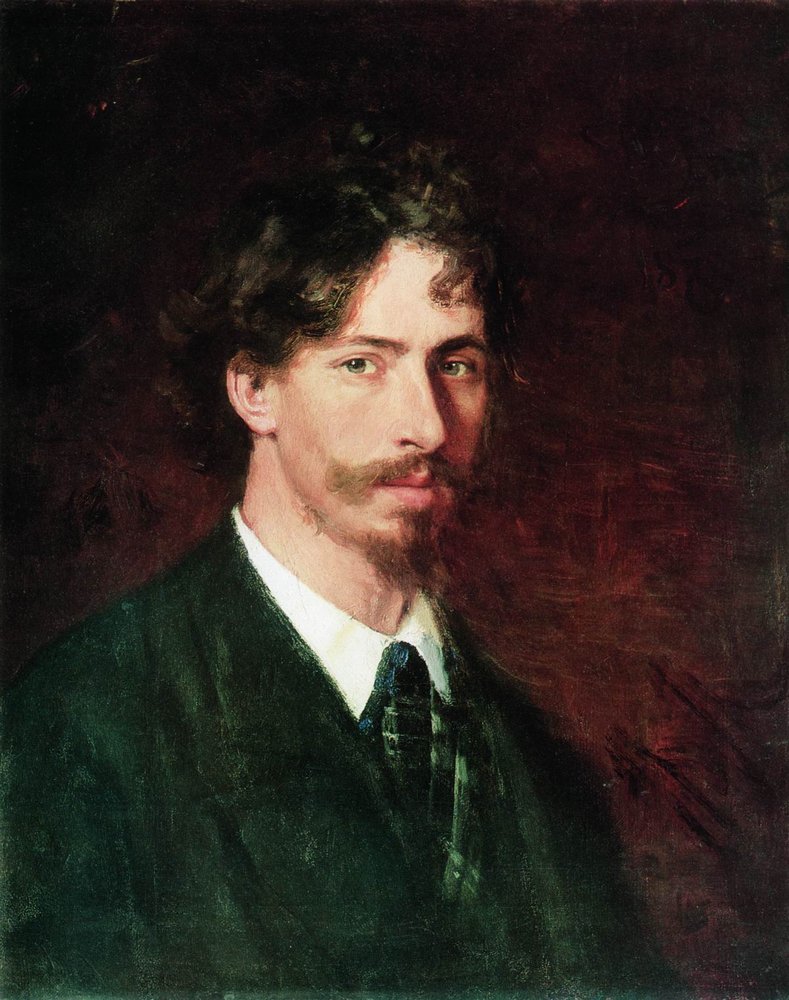

Despite the turbulence of the times, by his sixteenth birthday, Pini, an admirer of renowned realist painter Ilya Repin, had produced artwork that got him a scholarship at the Odessa Art School. Opened in 1865, this advanced school for aspiring artists, also known as the Odessa Art College, was a private institution that counted the Tolstoy family as one of its sponsors and served as a preparatory school that provided a diploma that qualified students for advanced art education. The school’s teaching staff were primarily artists who were members of the Society for Southern Russian Artists. Though they represented artistic movements that were more traditional, even the most conservative art teachers on the staff were open to educating outstandingly talented students with an independent air that was often considered radical and even unseemly. For these students, new ideas and directions, including that which became known as Russian avant-garde, became a passion.

Unlike other art schools in Czarist Russia where numerus clausus prevented most Jewish students from applying, the Odessa Art School had no such restrictions. By 1904, more than 60% of its student body were Jews, many of whom were born in small shtetls and some of whom would go on to become prominent and influential artists with worldwide recognition. By the time Litvinovsky began his studies there in 1910, among the alumni, or those who overlapped with Litvinovsky, were Leonid Pasternak, Yakov Chernikhov, Teofil Fraerman, Nathan Altman, Isaak Brodsky, Iosif Shkolnik, Amshey Nurenberg, and many others.

For a young man like Litvinovsky, Odessa was a dream come true. By the early 1900s, the city on the Black Sea was a vibrant and cosmopolitan hub, where the air vibrated with the echoes of Europe. A cityscape adorned with European architecture, Odessa was a melting pot of cultures, with a large Jewish community that by 1897 reached approximately 37% of the population.

For the artistic scene, Odessa provided freedom of expression previously shunned by Russia’s conservative artistic society. A year prior to Litvinovsky’s arrival in Odessa, a new art exhibition took the city by storm. Initiated by artist Vladimir Izdebskiy, himself a graduate of the Odessa Art School and a close friend of artist Vassily Kandinsky, Izdebskiy organized an international art exhibition of over 700 works from 150 masters. They included Russian artists, French artists from the School of Paris, members of the avant-garde group “New Artists’ Association Munich” as well as many others. The lineup represented the latest innovative artistic movements, from realists and impressionists to fauvists and cubists. More importantly, the exhibits emphasized the crumbling of traditional boundaries as artists sought new ways to express their inner visions. Though not without opponents—the great Ilya Repin, for example, was fiercely against—the exhibition received extensive coverage in Odessa and the international press.

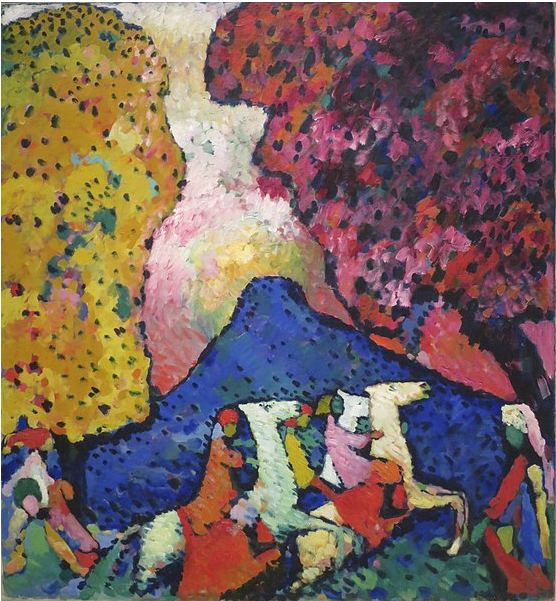

Known as the “Isdebskiy Salons”, the success of the first exhibition was quickly followed by the second seven months later, with 440 exhibited works by artists from Russia and Germany. Kandinsky, who emerged as a trailblazer in the seismic shift that the art world was experiencing, showed fifty-four pieces, including “The Blue Mountain”, a work that stood as a testament to his approach of weaving music, theory, and spirituality into his canvases and his belief in the transformative power of art. Himself a member of the Society for Southern Russian Artists from 1898-1910, in the exhibition catalogue Kandinsky also featured his commentary on influential Austrian-born artist and composer Arnold Schoenberg’s treatise “Content and Form”, in which he emphasized the interconnectedness of color, shape, form, and music as the only way for art to convey life and meaning.

There is little doubt that the young and impressionable Pinchas Litvinovsky absorbed the excitement and ideas of the passionate emerging artists and the new trends being born in front of his eyes.

This article is the second in our series “Rediscovering the Past, Empowering the Future” - Join us on a captivating journey through the life and legacy of Pinchas Litvinovsky.

This article draws from chapters of David Rozenson’s essay, “Rediscovering the Past, Empowering the Future: The Pinchas Litvinovsky Exhibition,” originally published in the exhibition catalogue that is available for sale here

Visit the Exhibition "You Must Choose Life – That Is Art: Pinchas Litvinovsky"

Main Photo: Odessa old CP with view to Russov (left) & Libman House, Odessa. Circa 1920.\ Wikipedia