Putting Jewish Women Back into History

Women in rabbinic roles are widely believed to be a XX century innovation, one which is still considered controversial by many orthodox communities. But in late XVI century Kurdistan, one Jewish woman managed to scale the height of rabbinic authority, leading her own yeshiva and corresponding with the top rabbis of her day.

Asenath Barazani’s father established a yeshiva to compensate for what he saw as a serious lack of scholarship in his country, intending to train young men who could be sent out to local communities to raise the level of Torah knowledge. He also extended this approach to his daughter Asenath who, as his only child, received the Talmudic education denied to most women until modern times.

“He only had a daughter and he just studied with her, no gender discrimination,” says Renée Levine Melammed, professor of Jewish history and an expert on the lives of crypto-Jewish women in Spain.

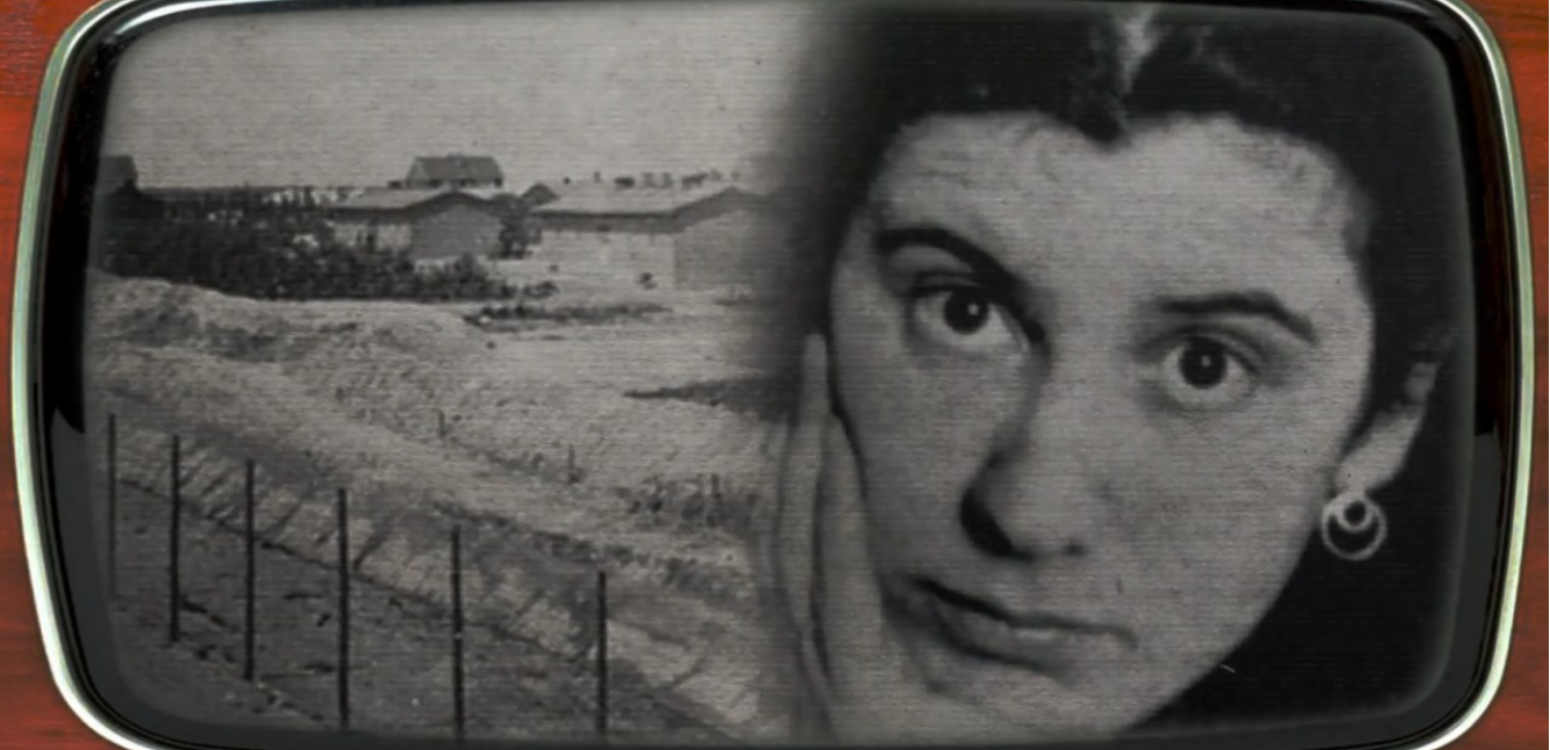

Women have long been left out of mainstream Jewish historiography, an oversight which Prof. Melammed has long worked to correct through academic publications and popular lectures. This includes a recent English-language series for Beit Avi Chai entitled Facing Adversity: Jewish Women throughout History, which focuses on three different women from Portugal, Salonika and Kurdistan.

When she came of age, Barazani married Yaakov Mizrahi, her father’s top student, who took over the yeshiva when the latter passed away. However, Mizrahi was more interested in his personal studies than in running the yeshiva, so this duty fell to his wife, who, surprisingly, “would go out and teach them and nobody objected,” Melammed says.

“And then he dies and Asenath takes over naturally. She’s got the seal of approval from her father and was trained by the greatest rabbi in Kurdistan at the time. There are letters written to her by rabbis in which they turn to her and talk to her as a peer. She was even asked by the Jewish community of Baghdad to send a scholar, someone she trained, because they needed a rabbi.”

Women are “absolutely underrepresented” in the Jewish historical record, says Melammed, adding that she has “spent most of my career working on this, as have some of my colleagues.”

But things are starting to change, and many people have shown interest in learning more about the contributions of Jewish women, a task made easier by the discovery of letters and documents by and about women in the Cairo Genizah.

“In the end,” Melammed says, “I want us to be represented not only in Jewish history but in general history as well.”

Photo credit: Wikipedia, I.am.a.qwerty

Model.Data.ShopItem : 0 8Also at Beit Avi Chai