Not many of the customers of his tiny convenience store in Holon knew that Bulgarian-born Avraam Benaroya had once been the founder of the Socialist Worker's party of Greece, the predecessor of Greece's Communist Party

On May 17th, 1979, a standard death notice appeared in Maariv, the mass-circulation Israeli daily. "We are heartbroken to announce the death of our beloved husband, father, brother, and grandfather Avraam Benaroya," it said. Signed: the bereaved family. The headstone, erected 30 days later above his resting place at the Holon municipal cemetery, was no less unobtrusive. Surrounded by other Balkan-born late residents of the working-class town, nothing would suggest that Benaroya, now dead at 92, was ever more than the ordinary Bulgarian-born, Holocaust-surviving corner shop owner he was known to be in his latter days. Few, if any, realized that he had been the founder of the Socialist Worker's party of Greece, the predecessor of Greece's Communist Party.

A fish out of water in the post-Ottoman world, Benaroya outlived his moment of glory by several decades. He came of age at the turn of the 20th century, when the Ottoman Empire was making its first foray into political modernity, a process cut short imminently thereafter, with the collapse of the Empire following its defeat in the First World War.

Just like many other of his compatriots, as a young man Benaroya left his hometown in the newly independent Bulgaria. His destination was Salonica (Thessaloniki), today's Greece's second-largest city, then still a major Ottoman port city; and, in the immediate wake of the 1908 Young Turks Revolution of which it was the epicenter, a fertile ground for progressive politics. "Bulgaria was a hub of socialism in the Balkans," says Dr Paris Papamichos-Chronakis, a historian of Modern Greek and Mediterranean Jewish History at Royal Holloway, University of London, and Benaroya, imbued with it, had big plans. The industrial city, with its sizable working-class population, was an ideal location for a skillful political organizer brimming with revolutionary zeal. A large proportion of Salonica's proletariat-in-waiting was either Jewish or Bulgarian, or both. For Benaroya, it immediately became a home away from home.

An Ottomanist through and through, Benaroya advocated for a "type of socialism that was borne out of his firm belief in the Ottoman project," says Dr. Papamichos-Chronakis. For him, the survival of the expansive, multiethnic and multilingual empire "was key to the promotion of his socialist vision." Against this backdrop, almost immediately after its creation, the Workers' Federation that he founded – known colloquially as Federacion, in Ladino – became a force to be reckoned with in Ottoman politics. It soon grew to be the umbrella organization of the biggest trade unions in the empire, and its messages resonated both in Istanbul and, following Thessaloniki's incorporation into the Greek state in 1913, in Athens. In the first national elections, held in 1915, the Federacion did well, sending two representatives to parliament (one of them, Alberto Curiel, was Jewish).

Everything that made Benaroya's politics successful under Ottoman rule turned against him in the wake of the First World War, to which he vehemently opposed. Thessaloniki had been brought under Athens' wing, and Benaroya resolved "that there's no turning back," says Dr. Papamichos-Chronakis. "He was ultimately persuaded that the future of his political project lay in Greek national politics." The failure to make gains in the Greco-Turkish war, fought after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, sent Greece on a jingoist spiral that did not spare the more progressive forces in national politics. The vision championed by Benaroya, the Bulgarian Jew, was now perceived as the antithesis to the nationalist agenda that gradually prevailed in what had by the early 1920s become the Communist Party of Greece – the same party that he set up in its former iteration.

In 1912, his heyday, Benaroya visited Athens to meet with the members of the socialist party. The organization, led by drab bureaucrats, all Greek Orthodox, was nothing like the bustling mass movement that he led in Salnoica. He was most appalled that instead of the obligatory portrait of Karl Marx, the walls of their offices were adorned with crucifixes. To his tacit dismay, now, after the war, these people were in charge.

A no less decisive factor in Benaroya's fall from grace was the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, whose shockwaves redefined socialist politics across Europe. Inspired by Moscow, the socialist Mecca, socialists around the world opted for hardline revolutionary politics. Benaroya's moderate, grass-roots, parliamentary socialism – in addition to his internationalist outlook – had less and less traction in his own party. Ironically, his famous knack for political organization – what had turned the Federacion into a massively popular movement – was a disadvantage in a party that consciously distanced itself from the masses and was bent on creating a Leninist vanguard. As before, the fact that he was Jewish and Bulgarian did not help either. In 1924, he was expelled from the party.

As a loyalist of the Second International, Benaroya was initially hostile to Zionism. Unlike his Eastern European peers, he had no experience of pogroms and antisemitism. "He didn't think there was a Jewish problem," says his son, Eliezer Benaroya, "but this changed after the Second World War." Like tens of thousands of his Jewish fellow countrymen, he was deported to the Nazi death camps. Unlike most of them, he survived. After the war he resettled in Athens, only to find that postwar Greece was even less conducive to socialist politics than before. The Greek Civil War of the late 1940s, essentially an attempted coup d'état led by the Communist Party and other movements, ended after a massive government clampdown on the opposition. Communism was outlawed and socialism – even the moderate version that Benaroya championed – discredited. It was then that the young Israel emerged as an attractive alternative. The Land of Socialism, he called it in an article he published in 1951 after returning from a visit there.

He made aliya in 1953 and settled in Holon, just south of Tel Aviv, where he made a living as a newsagent. "In Israel, he wasn't a very political man," says his son Eliezer, who now lives in the US. A member of Mapai, he was campaigning for Ben Gurion's ruling socialist party, delivering speeches in Ladino at election rallies. But he never ran for office. "My father spoke 16 or 17 languages, but he never mastered Hebrew. That's why he wasn't more involved in Israeli politics," says Eliezer Benaroya.

His steady descent into anonymity was interrupted in the 1970s. Aggelos Elefantis, an exiled Communist intellectual, took interest in Benaroya and tracked him down in Israel. After the military dictatorship was toppled and socialism was again a legitimate worldview in Athens, Elefantis decided to publish two books by Benaroya – one was his memoir from the 1930s, and the other an edited volume of his political writings penned while in Greece. Benaroya, whose ideas found a renewed echo as European Communists were becoming gradually disillusioned with the Soviet Union, again became a household name among the Greek left. "In 1978, a delegation of journalists from the political magazine Vima came to Israel for a week and interviewed him for many hours, in preparation for a series of articles dedicated to him," says Eliezer.

However, says Dr Kostis Karpozilos, the former director of the Contemporary Socialist Archives in Athens and a candidate for the New Left party, "his expulsion from the party created an ambivalence that continued to haunt his legacy. The whole ethos of the Communist Party was built on their image as a national resistance movement, which they developed to fend off accusations that they were not patriotic enough." Admitting Benaroya back into their pantheon would be conceding that the founding father of the party had stood for very different principles from theirs.

In later years, says Dr Karpozilos, Benaroya's legacy benefited from a new awareness of the broader history of Greek Jews. Salonica, once the largest Jewish city in Europe, is now celebrated as a symbol of Greece's buzzing multiethnic past. "We've reached a stage in the Greek left where the national focus has been subsumed by an interest in multiculturalism," Dr Karpozilos notes. But here too the ambivalence remains: Benaroya’s life in Israel, and his support for Zionism in his latter years, have been a tough pill to swallow for the traditionally pro-Palestinian Greek left.

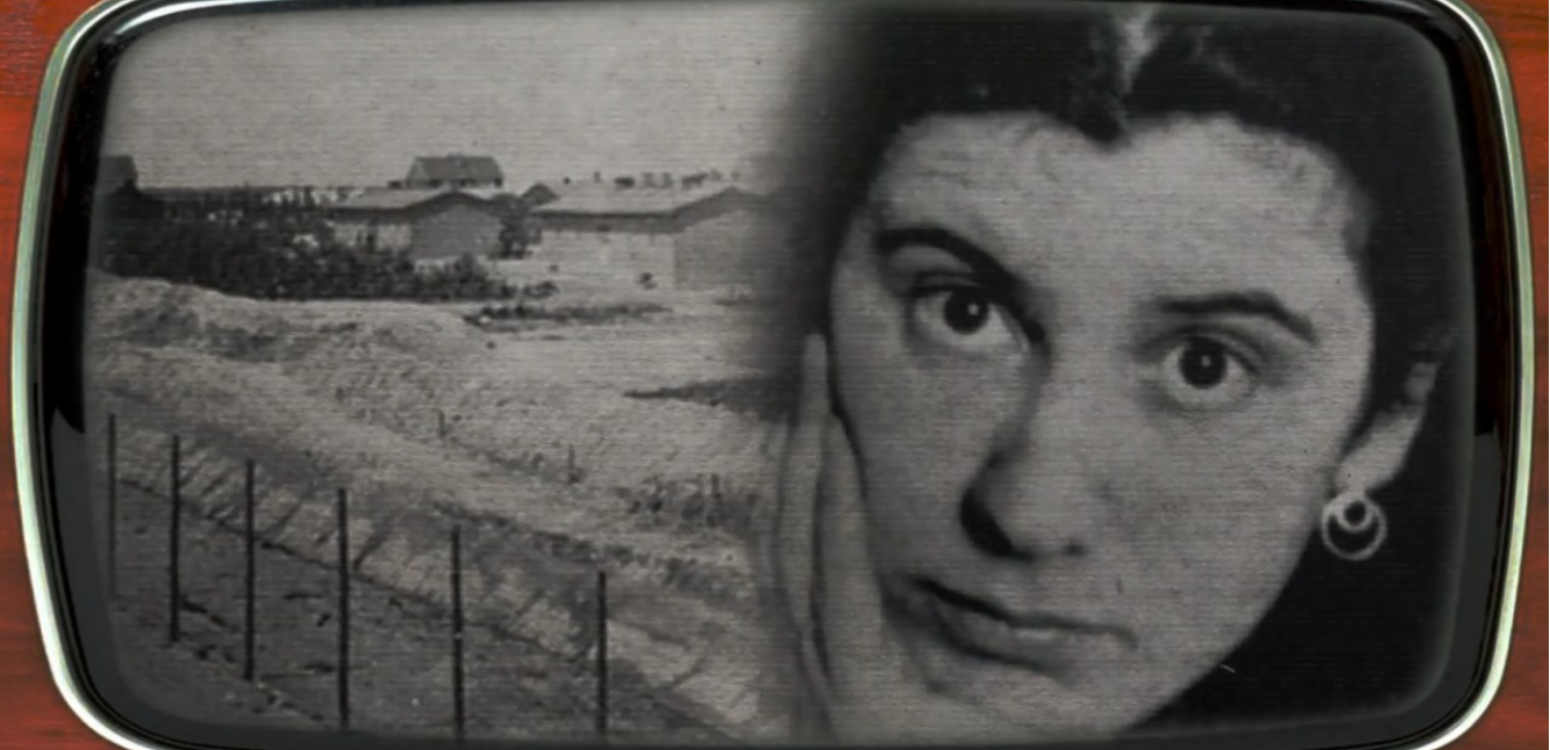

Main photo: Avraham Benaroya\ wikipedia