According to Chazal, is there absolute beauty or do aesthetics depend on culture? A conversation with researcher and artist Dr Tamar Kadari

What did the Chazal, the Jewish sages, think of beauty? What was the beauty ideal in the Land of Israel and in Babylon in the first centuries of the common era? Is beauty an objective concept? Every time Dr Tamar Kadari, a senior lecturer at the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, talks about the sages’ concept of beauty, she is met with raised eyebrows: “I am engaged in the study of the Midrash and Aggadah and am particularly interested in the attitude of the sages towards aesthetics and beauty. This always surprises people, because the common perception is that the sages did not take this issue seriously. Students quote the verse ‘Charm is false and beauty is futile’ and assume that it sums up Chazal’s position on the matter, but the truth is that when I started reading the sages’ writing without prejudice, I discovered that there are many texts that testify to the exact opposite: Chazal were very sensitive to aesthetics and beauty and this issue was no less important to them than it is to us today.”

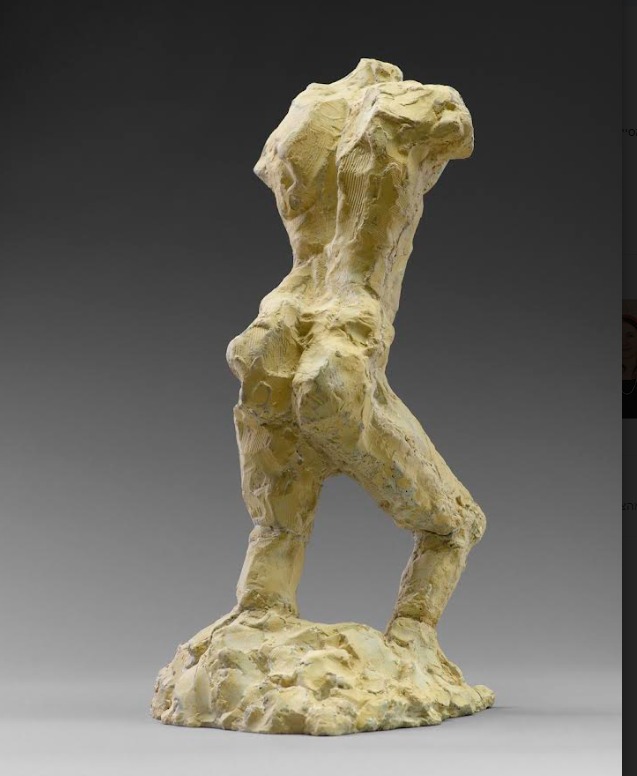

Besides being a researcher, Dr Kadari is also an artist and sculptor who has participated in exhibitions in galleries in Jerusalem and Tel Aviv. Her work focuses mainly on the human body. “I sculpt the human body, and therefore, naturally, I am interested in the attitude of the sages towards the human body, how they perceived human physical beauty – of men and women. The sources prove that Chazal were also aware of the beauty of architectural structures, the beauty of nature and the magic of art. In my study of the sages’ relationship to the human body, I actually merge the two areas that interest me, expressing two sides of my professional personality. When I approach my research, I also bring an artist’s point of view with me, and things also work in the opposite direction – the contents of the midrash are reflected in the sculptures I create.”

“I find a lot of similarities between the story of the creation of Adam and Eve and artistic creation. The midrash describes God as an artist who is debating how to create, who uses ‘dust from the ground’, who sometimes destroys his creation and then rebuilds it, just like a sculptor who works with clay, creates and destroys, adds and takes away."

How do Chazal perceive beauty?

“Today, the widespread consensus is that everyone has their own taste, that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. But there are also other philosophical takes on beauty. For example, according to one, it is possible to explain what is beautiful using mathematical tools – a certain relation between the features is perceived by the human eye as a beautiful. Although we don’t know if Greek sculptors based their works on mathematical formulas, we all look at the ancient statues and agree that they are the embodiment of beauty. So there are different answers to the question of whether beauty is in the eye of the beholder or whether there are beauty conventions that everyone accepts. Nowadays there are still newspapers that annually publish a list of the most beautiful women and men around the world. Such a list reflects the idea that there are clear beauty standards. It’s amazing to see that so many people from different parts of the world think that a certain person is handsome. Among the Chazal writings, you can find evidence of both approaches. I mean, you can literally find evidence of absolute concepts of beauty – for example, when the Babylonian Talmud lists the most beautiful men of all time or the four most beautiful women in the world. These lists traverse continents, cultures and times and reflect the concept of beauty being objective and not dependent on the eye of the beholder.

On the other hand, there are sources that reflect a different approach, according to which beauty depends on the place where we live and the sights we are used to seeing. There are also sources that address the fact that certain physical conditions, for example poverty or life challenges, can spoil beauty. There is also mention of the fact that it is possible to enhance the beauty of a woman who lost it by investing in it.”

Can you give us an example of a midrash that interests you in this context?

“It is amazing to discover that one of the figures Chazal considered to be the most beautiful is Adam, even though it is not mentioned anywhere that the first man was a beautiful creation. The midrashim praise Adam’s beauty; they say that he and none other than the one who created him – God in his own glory – were alike as two drops of water. The words are explicitly stated in the verse ‘Let us make man in our image, after our likeness’, and the sages understood this literally. Regarding the beauty of the first man, the sages in Bereshit Rabba quote a very beautiful parable about a king who was traveling in his magnificent chariot with the minister in charge of the district. The townspeople wanted to praise the king, but they looked at the two figures inside the carriage – the king and the minister – and were unable to distinguish between them. When the king realized what was happening, he threw the minister out of the chariot, so that everyone knew who the king was. The parable refers to God creating Adam in his own image, so much so that the angels got confused and did not know who they should praise. In the end they made a mistake and started praising Adam. When God saw that, he put the first man to sleep, and since sleep is a human attribute, the angels realized that he was a human being, not God himself. The intriguing question here is why God created man in his image. Why did he create a figure that would compete with him and even threaten his position?

It is often said that the artist always sculpts or paints themselves, and it does not matter who was the model or the inspiration for the work. Even when another figure stands in front of the artist, the result resembles the latter. In the story of creation, God creates the man, and the man ends up resembling his creator. Chazal interpreted the words ‘after our likeness’ as outward resemblance. In the list of the most beautiful beings of all time, the first man is in second place, and above him, at the top of the list, stands God. One can see here the influence of the Hellenistic view that God possesses perfect beauty. The first man created in his image is actually a copy of him, therefore he is the most beautiful human being of all time. Similar to an artistic reproduction, the value and beauty of the work is determined by proximity to or distance from the source."

Is there something that today is considered beautiful, but the sages would not have agreed, and vice versa?

“One of the questions that most concerns us as a society in recent years is the problem of obesity and excess weight. That is why it is intriguing to check what Chazal considered more beautiful – a fuller look or a thinner look? Rabbi Yochanan, who lived in the third century CE and was the head of the Tiberias yeshiva, is considered an exceptionally beautiful figure. The Babylonian Talmud praises his beauty, and in the same breath also describes him as a fat man with an extremely large belly. It may be that in a society where there is a shortage of food, a person who has means and can afford to indulge in good foods and invest in fancy clothes is considered a symbol of beauty. On the other hand, in the sources from the Land of Israel, for example, in the Genesis Apocryphon from the first century BCE, Sarah, who is considered one of the most beautiful women of all time, is described as having long thin fingers. It may be that there is a difference between the beauty ideals in the Land of Israel and those in Babylon.”

We are in an age where the pursuit of beauty is almost obsessive. Do you think the sages can offer us some wisdom to help deal with that?

“In Chazal’s writing one recognizes a desire to moderate the importance of external appearances. For example, Midrash Pesikta de-Rav Kahana tells of a Talmudist Rabbi Abbahu, one of the most beautiful figures of all time, who returned from Caesarea with a radiant face. The students asked Rabbi Yochanan what happened that made Rabbi Abbahu’s face so radiant. They suggested that he might have found a treasure when he was in Caesarea, a city on the seashore where ships from foreign countries were anchored. Rabbi Yochanan answered that Rabbi Abbahu must have heard some new Torah. These suggestions made by the students and the rabbi are a kind of mirror that reflects the opinion of each of them regarding the question of what would make their faces light up. And then, when Rabbi Abbahu came to Rabbi Yochanan, he shared that when he was in Caesarea, he heard an ancient Tosefta, that is, important and ancient educational knowledge that was passed down orally and was almost lost. The midrash ends with the verse ‘A man’s wisdom shines on his face’.

I think that the explanation that the light on Rabbi Abbahu’s face stemmed from his learning is a message to us. The midrash tells us that although Rabbi Abbahu was one of the most beautiful sages, the light of his face, the light that spread around him, originated from his learning and not from his external beauty. The beauty he radiated came from the inside – it was a deep erudition that illuminated the outside. This story and the verse ‘A man’s wisdom shines on his face’ convey the notion that beauty is only an external matter; they indicate that there are also internal qualities that illuminate the faces of those who might not be objectively outwardly beautiful.”

So it’s not just an external matter.

“Another attempt to moderate the importance of external appearances is found in the tractate Ta’anit, in the story of Rabbi Yehoshua ben Hananiah, a sage who was very ugly. The Talmud describes how the emperor’s daughter insulted him and said, ‘Magnificent wisdom in an ugly vessel’, that is, how can you be both so ugly and so smart? And the conclusion of the story is that beauty spoils wisdom. That is, if Rabbi Yehoshua was handsome, he would not have been that smart. This concept seeks to address the centrality of beauty, according to which beauty sometimes comes at the expense of wisdom. After all, we have before us a wise man who became so wise due to his ugliness. Despite the fact that one can find in Chazal’s writing many different approaches to aesthetics and beauty, even the stories that seek to reduce its importance or provide another answer in its stead, do not detract from the strong influence and the central place that the sages attributed to it.”

This article was originally published in Hebrew.

Main Photo: Wikipedia