The story of two extraordinary illustrated Aleph-bet books: one was published only after the death of the illustrator, the other never saw the light of day

Jewish communities used to celebrate the first day of school by giving the child sweets, as in the zuckertüte tradition (literally meaning “a bag of sugar”) or, at cheder, by allowing them to lick honey off a board or a piece of paper with the Hebrew alphabet on it. In the Cairo Geniza (a collection of ancient Jewish manuscripts from the IX-XIX centuries that was discovered in the attic of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo), you can see evidence of the way Jews learned and practiced the Hebrew script a thousand years ago – by repeating letters, coloring letters in and copying out the sentences in which all of the 22 Hebrew letters appeared.

And so, for generations, the method of Jewish education remained the same: after memorizing the shapes of the letters and learning to read, the pupils at cheder would memorize chapters of the Torah and of Rashi, and from there they progressed to the study of the Torah and the Talmud. Hebrew remained exclusively a sacred language.

Victoria Hanna – The Aleph-bet song (Hosha’ana) Official video

All this changed, at least for some of the children in the Jewish communities, when Moses Mendelssohn, father of Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment movement, and his students sought to establish proper schools with textbooks for all subjects and to make Hebrew into a language that could also be used in secular life. From that revival of the language literature grew.

And so, in 1778, the first Jewish school, established according to Haskalah ideals, was opened in Berlin with the support of the government. Following that, special Hebrew-language textbooks for children were created.

The first Hebrew reading book for teenagers appeared only towards the end of the XVIII century. The book, “Avtalion” by Aaron Halle-Wolfssohn, is considered to have been the work from which the history of Hebrew children’s literature began.

Later, during the First Aliyah, the first schools where Hebrew was taught were established in the Land of Israel. The need for Hebrew children’s books grew, in the backdrop of the revival of the language and it being more and more widely used in day-to-day life.

Secular children’s books in Hebrew appeared in Russia at the end of the XIX century, but only at the beginning of the XX century did first Hebrew picture books appear. Their pioneering creators were Jewish people of letters who grew up without anything to read in Hebrew and so sought to create modern richly illustrated Hebrew books for the children of Israel.

In 1892, Martha Gertrud Freud was born in Austria to the well-known Freud family – she was Sigmund Freud’s niece. At 15 she decided to change her name to Tom. From a young age Tom painted and even staged performances based on her paintings, together with her sister Lily who was an actress. Tom studied art in Berlin and London, and in 1918, after the publication of her first book “The New Picture Book”, she moved to Munich to join her sister there.

In Munich, Tom met the renowned Kabbalah scholar Gershom Scholem, and entrepreneur, publisher and S. Y. Agnon’s patron Salman Schocken. She showed Schocken an alphabet book she was working on. It was the first textbook she created. It was supposed to be rich and colorful, aimed at the first generation of children to grow up with Hebrew as their mother tongue. The concept was to include the 22 letters of the Hebrew alphabet along with 22 poems, with Tom’s drawings of each letter being riddles which needed to be deciphered to discover the letters themselves.

Schocken, who at the time served as head of the Culture Committee of the Zionist Organization and was looking for books that would reflect the Jewish past as well as the evolving Hebrew culture, loved Freud’s idea. He also loved her unique illustrations for this project, which were based on biblical stories, combining Egyptian and modernist styles and drawing on a comprehensive study of hieroglyphs. They were exactly what he was looking for.

Schocken sent the illustrations to S. Y. Agnon and called him to come to Munich to write the rhymed poems that would accompany each letter. Agnon was not enthusiastic about the idea of coming to Munich, nor the idea of writing poems for existing illustrations. He called it “preparing the foot for a shoe”. But he tried to provide a rich multi-layered text to match Tom’s illustrations, combining passukim and midrashim.

When it was ready, Schocken didn’t hurry to publish the book. Part of the reason was that the Culture Committee did not have the budget for printing in color – the feature that Tom insisted on and fought for. However, probably Schocken’s main consideration was that he did not think the end result to be suitable for children. Schocken kept delaying the publication at the book, and it was eventually shelved.

.jpg)

Agnon left Munich and got married, while Tom left for Berlin and met the young bibliophile and publisher Jakob Seidmann (who translated “The Zohar” into German). Having married Jakob Tom adopted the double-barrelled surname Seidmann-Freud. The couple had one daughter, Angela, and together with Hayim Nahman Bialik founded “Ofir”, a boutique children’s publishing house where Tom was responsible for the artistic side and illustrations, while Bialik translated and wrote original texts as inspired by Tom’s artworks. In fact, a few of Bialik’s poems for children that we know today were written for and inspired by Tom’s drawings. Four books were published by Seidman-Freud and Bialik as part of their collaboration, and they are still considered classics of Hebrew children’s literature.

Tom continued to work on other books in German and Hebrew. As an illustrator, she had a revolutionary pedagogical approach, promoting playfulness and imagination. Learning, she believed, happens “unconsciously” when the child “is immersed in their world”. These ideas were expressed in her illustrated German textbooks, which were part of the compulsory reading in the German education system until the Nazis came to power.

In the years of the economic crisis preceding the rise of the Nazis, Bialik returned to Israel, the “Ofir” publishing house was closed, and Tom Seidmann-Freud and her husband found themselves in debt and terrible financial strife. Jakob Seidmann found no other way out than to take his own life. Tom Seidmann-Freud sadly died a few months after him. Their daughter Angela was raised by Tom’s sister Lily, and she immigrated to Israel at a young age, where she changed her name to Aviva. The archive of Tom Seidmann-Freud, including some of her illustrations for her alphabet project with Agnon, were stored away and are still in Israel today, held by her granddaughter Ayala Drori.

To this day, “The Alphabet Book” (as it might have been called) has never been published. Maybe one day Seidmann-Freud’s wonderful book will see the light of day. In the meantime, one can find comfort in the fact that while working on it, she discovered her favorite technique – that of pochoir, hand-painted stencilling. This made her ingenious illustrations so unique, recognizable and luminous, even about a century after her death.

And while Seidmann-Freud’s version was never published, upon Agnon’s death in 1970, his daughter Emuna discovered two notebooks in his estate containing his alphabet poems written in 1920. In the early 1980s, Agnon’s alphabet poems were finally published, under the name Sefer Ha-otiot (“The Book of Letters”), however not with Freud’s original illustrations – they were illustrated for this edition by Yoni Ben Shalom. This is actually the only picture book written by Agnon.

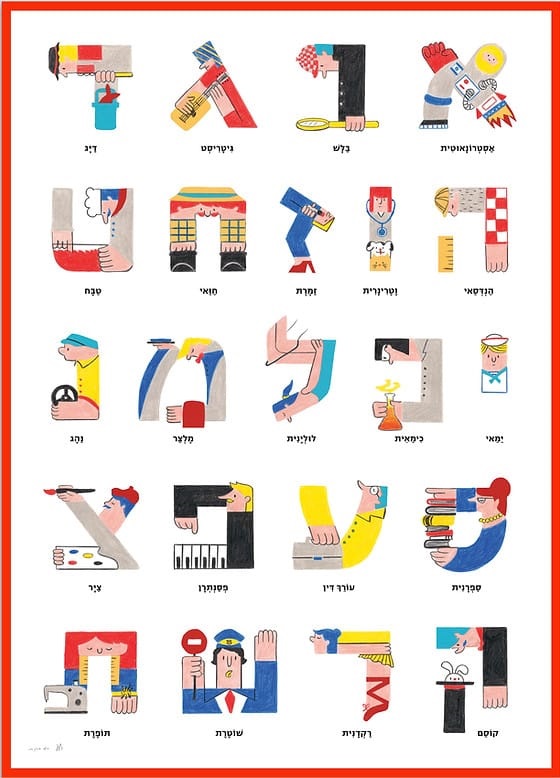

Another beautiful alphabet book is Miktso-0t ("Profession-a-letters – Letters Go to Work") illustrated by Hagar Bareket, a promising young designer and illustrator who passed in 2020, when she was only 27 years old. Like in the Freud-Agnon collaboration, in this project also, the illustrations preceded the text.

Hagar graduated Shenkar College’s School of Visual Communication with honors. She majored in illustration, print and animation and won many awards during her studies. Her clever and witty illustration "Profession-a-letters" explored each letter of the alphabet as a profession, and represented Shenkar College at the Bologna Children's Book Fair in 2018.

The Hagar Bareket Foundation was established by her family in 2021 in her memory. The foundation promotes excellency in design and illustration by granting scholarships at Shenkar College for Design and in collaboration with various initiatives in design and illustration in Israel. Hagar left behind her incredible and rich works of art which are sold in several Israeli design stores. All proceeds go to the foundation into accomplishing its mission and fulfilling its vision of “talent supporting talent”.

Recently, the foundation published the children's book "Profession-a-letters – Letters Go to Work" featuring Hagar's illustrations, and author Shoham Smith's skilfully crafted rhymes, which were written specifically for the book. The book was designed by Noa Schwartz, Hagar’s teacher at Shenkar.

Hagar wished to illustrate a children's book, and "Profession-a-letters – Letters Go to Work" is a way of fulfilling her wish.

Special thanks to Ada Wardi and Marit Benisrael for their extensive research on Tom Seidman-Freud, published in “The Book of Tom” (Asia and Mineged, 2022); to Ayala Drori, Tom Seidman-Freud’s granddaughter for the permission to use illustrations and family photos; to Racheli Edelman, head of Schocken Publishing House and to the JTS-Schoken Institute for Jewish Research for permission to use illustrations from “The Letters Book”; and to Hagar Bareket Foundation for permission to use her artwork.

For more Aleph-bet, see Beit Avi Chai’s Shalom Kitah Aleph Festival

Main Photo:Tom Seidmann-Freud from Die Fischreise Pl.09 (1923)