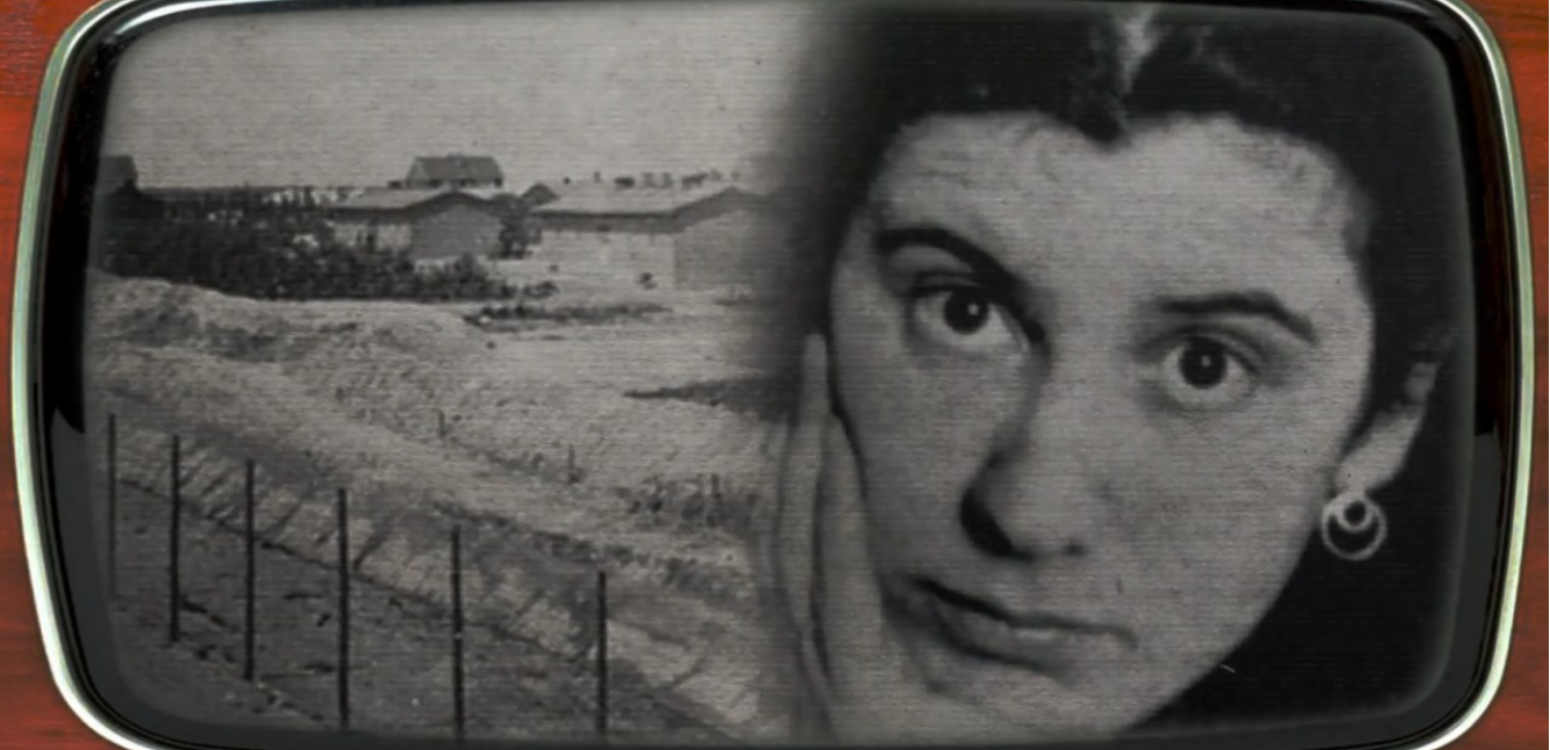

Simone Weil: The Philosopher Who Found Meaning in Suffering

Simone Weil, who devoted herself to the search for truth in a world of pain and injustice, turned her own suffering into the cornerstone of her philosophy

Simone Weil is one of the extraordinary figures in the world of Western thought, a philosopher whose life was a constant struggle between the body and the spirit. Her life moved on the axis between deep thought and action, between the search for truth and personal sacrifice. Instead of creating a promising philosophical academic career for herself, Weil chose to work in factories alongside the workers; to learn from them about poverty, about suffering, about obedience and work and turn her experiences into a philosophy that arises from the things themselves.

Weil, born in Paris in 1909, grew up in an intellectual Jewish family, but very quickly deviated from the expected path. She refused to settle for academic honors and aspired to live in the world, not above it. In an unusual move for a woman of her position, who came first in her class in “General Philosophy and Logic” and left Simone de Beauvoir in second place, she chose to take a one-year break from teaching and work in factories to better understand the plight of the workers. This was not purely “field research”. The hard work, the long days and the encounters with the world of exploitation and poverty exposed her to truths about human dignity that she could not have learned through books alone. Weil was not only a witness to the suffering of others; she lived it.

This experience engraved deeply in her consciousness the idea of pain and suffering as formative forces. For Weil, suffering is not something to be avoided – it is an existential essence that allows a person to reach spiritual and moral heights. To many, this idea sounds paradoxical, even provocative, however, Weil believed, perhaps more than any other thinker in the XX century, that it is precisely from humiliation, poverty and pain that one can reach spiritual elevation. She aspired to extract meaning from suffering, and did not succumb to the idea that material life is the pinnacle.

Weil’s most famous book, “Gravity and Grace” (French: La Pesanteur et la Grâce), explains the way she perceives life. She believes that life is a struggle between earthly gravity – the one that pulls us down, into the material world and passions – and divine grace, which is able to lift us up. If one manages to break free from these shackles, Weil claims, one can experience true spiritual freedom.

Weil’s life is a story of extreme commitment to her ideas, so much so that Albert Camus said of her that she is “the only great spirit of our time.” In 1943 Weil was diagnosed with tuberculosis. Being ill, she had to rest and eat well, but for reasons of solidarity and ideology, she reduced her diet to what she believed the people in occupied France were eating. She often refused to eat at all. Researchers discuss the question of whether it was indeed an ideology or whether self-starvation was the result of mental illness. Either way, weak and starving, Weil died at the age of only 34, leaving behind an intense, brilliant and wide-ranging philosophical legacy.

Weil is not the typical academic thinker. She insisted that her thoughts would not remain between the pages of books, but would pass through the body, through the most real experiences of life: through suffering, struggle and pain. Perhaps this is why her ideas resonate even today, and her philosophy remains unique in the landscape of XX century thought – philosophy that is not only the fruit of cogitation, but of a life dedicated to the question of how one can truly be human in a world of suffering and injustice.

This article was originally published in Hebrew.

Model.Data.ShopItem : 0 8

Also at Beit Avi Chai