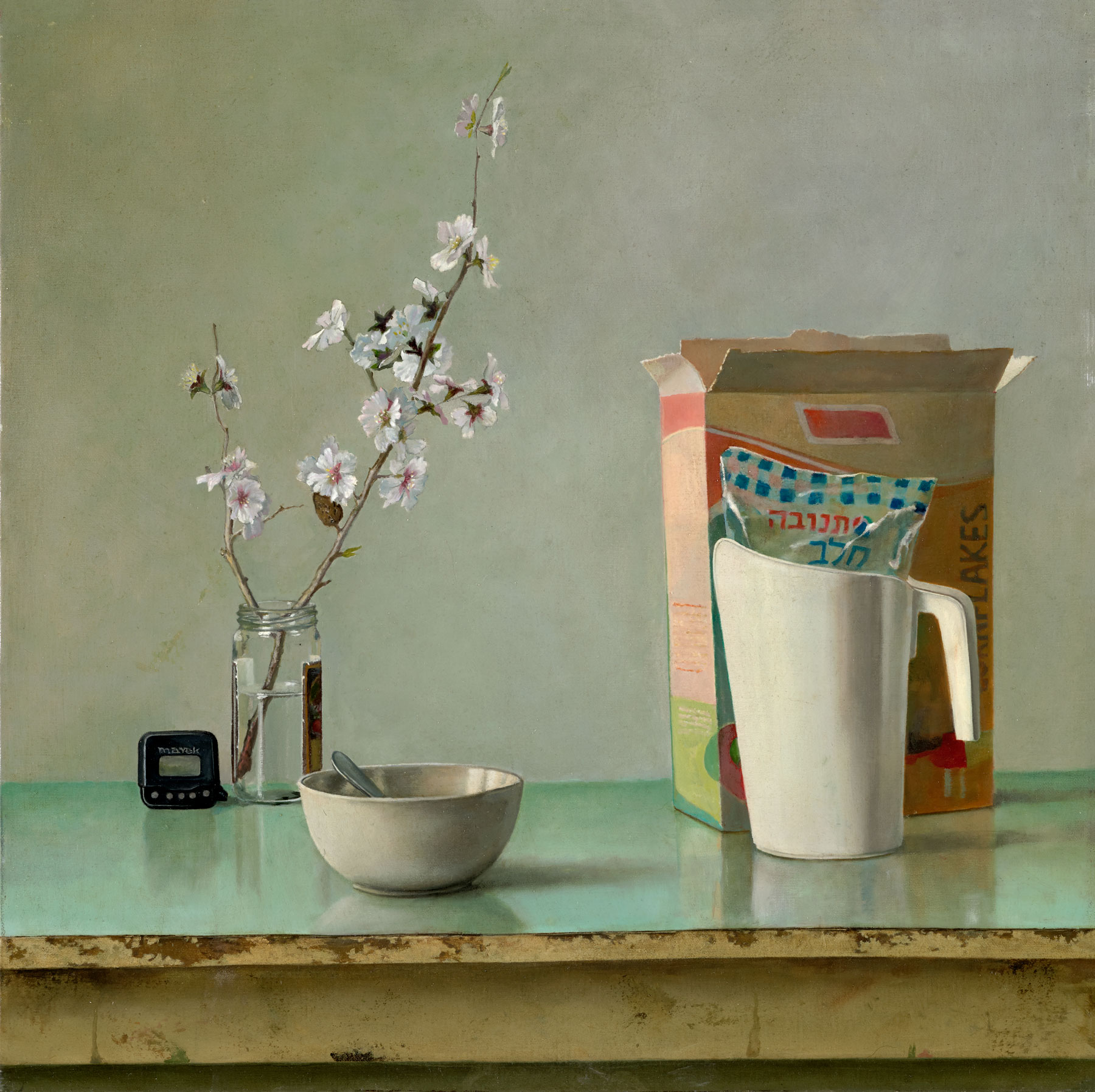

Breakfast in Katamon, Oil on Canvas, 65 * 65 cm|Marek Yanai

The Threshold. Marek Yanai has been painting Jerusalem’s thresholds for over 50 years: gateways and fences, doors and gates, stairwells and windows. Thresholds are liminal spaces, neither indoors nor outdoors, but on the verge of both, somewhat forsaken, suggesting alluring secrets in both directions. The imagination strives to fill in missing details. Who climbs these stairs on their way home? What awaits behind the gate? Why is this door, or that one, or both, and yet another open?

Yanai’s work seems explicit, precise, clear and unambiguous. Figurative paintings, easily deciphered: an armchair, a portrait of an elderly gentleman, a view of Temple Mount. But his repeated depictions of these thresholds reveals blurred edges between the visible and the hidden. There are only traces of human presence: a letter protruding from a letterbox, the wear left by feet on veteran steps, an opened newspaper. Other details include banisters, window bars, doors, a doormat, a clothesline, glimpses of trees and planters, colorful Armenian tiles, plaster, stones, a keystone at the apex of a masonry arch. Seemingly banal, impersonal details fill in the void, collectively portraying entire realities. Moments of prevailing light penetrate space, guiding the viewer’s eye.

Kiryat HaYovel, Oil on Canvas, 114 * 161 cm| Marek Yanai

Jerusalem. Yanai traces borderlines between neighborhoods that were once on the frontier between forces and still preserve walls and gates. Jerusalem’s thresholds are part of a larger project in his work, documenting the city, its views, particulars, and people in oil and watercolor.

Yanai joins a genealogy of artists drawn to depict Jerusalem, documenting pilgrims over the centuries up to modern painters like Ludwig Bloom, Anna Ticho, Shmuel Haruvi, Leopold Krakauer, and others.

Like his predecessors, Yanai is attracted by the hills bordering Jerusalem and by the Old City and her surroundings. But unlike other artists, his gaze does not avoid less attractive aspects of the contemporary city, such as the concrete housing projects of Jerusalem’s new and less affluent neighborhoods. The large blocks of Kiryat Hayovel are represented in a light and at angles that evoke the majesty of the walls of the Old City. His canvasses alternately integrate and resist the natural landscape, sometimes both simultaneously. Concrete walls at the city’s entrance seem to grow directly from the green slopes. Below them, .a spring feeds a pool surrounded by prickly pears among the ruins of the village of Lifta.

Marek Yanai positions Jerusalem on the threshold between heaven and earth. A city of stone, with belltowers, solar panels, water tanks and gas cylinders, at the intersection of urban development and vestiges of natural landscape. Together they compose, in the words of poet Yehuda Amichai, the “in-between Jerusalem”, a recurring motif in poetry about Jerusalem, often set in the same spaces painted by Yanai. “Why is Jerusalem, Yerushalayim always too, the heavenly and the earthly?” asks Amichai in his cycle “Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Why Jerusalem?” He concludes:

I want to live in the in-between Jerusalem,Without banging my head up above or gashing my feet down below.[1]

Shifting boundaries define the in-between Jerusalem that, in both Amichai’s poetry and Yanai’s paintings, reveal Jerusalem from the perspective of those living between these lines, within history, carrying groceries home for dinner. The splendor of holiness blends with the mundane, the sublime with the prosaic.

Mood Board, Oil on Canvas, Dubi Shiff Art Collection - Tel Aviv, 70 * 100 cm|Marek Yanai

The Studio, Talpiot. Yanai rents a studio in the Talpiot industrial zone, between two branches of the Rami Levy supermarket chain. The scent of frying oil from nearby falafel stands accompanies visitors up the stairs towards the main space in which he paints, teaches, and stores his works. Through the window is a motorcycle workshop, on its roof a surreal installation of motorcycle carcasses. This is Yanai’s daily view, a scene that he never paints, a bizarre image that is real, yet very distant from him.

As Yanai searches for a particular painting, I look around the studio, occupied by still-life leftovers from last night’s lesson, an assortment of old chairs in a semi-circle, a tea pot, tea, and coffee. As he rummages through his canvases to locate a particular painting, I focus on one he calls, “The Board of Inspiration” . It incorporates reproductions of works by others, with images that imitate the work of Ori Reisman and Meir Appelfeld, “Angelus Novus” by Paul Klee, self-portraits by Leonid Balaklav and Egon Schiele, color fields by Marc Rothko, photographs of the artist's children. Surprisingly, like the motorcycles on the neighboring roof, most of these images are very different from Yanai’s style.

Winter at the Moon Grove, Watercolor on paper, 48 * 65.5 cm|Marek Yanai

Rocks at the Moon Grove, Watercolor on paper, 65 * 101 cm|Marek Yanai

Moon Grove. When weather permits, Yanai takes groups of students for open-air lessons. Between the German Colony and Talbiyeh, a pine grove managed to survive, at least for now, the rapacious real estate developers who have left their marks all around. According to a local fairytale, the grove was named after the large, white, stone outcroppings frequently rising out of the soil, creating a resemblance to the surface of the moon. But the moon seems also to imply refuge. A refuge for trees, a refuge for nesting falcons and owls, a refuge for recluses and family picnics, and a refuge for at least two eccentrics who have been living here for years.

Each morning and evening, on my way to and from work, when I pass through the moon grove, I frequently see Yanai with his students: a small flock of painters spread throughout the grove, setting up easels, examining canvases. Occasionally, Marek paints them as they work. Sometimes, he paints the trees as if they are human figures, with multiple elbows (Pages 102-105). In two watercolors, we see Yanai’s interpretation of the changes wrought upon the grove by the seasons : In the first, winter dyes the ground green and a slight fog shrouds the trees and stone houses, so that even the ugliness of the Mishab Tower, standing tall at the edge of the neighborhood, is blurred; in the second painting, the green has already turned yellow under the summery sun. The wakening pines welcome the light shining on their treetops, and the large stones that have been cleared to the edges define nature’s border for nature as well as that of the painting. In these works, the moon grove resembles the thresholds: a passage, seemingly empty, but Yanai chooses to linger and attach meaning to the life and secrets being created inside.

Breakfast in Talbiya, Oil on Canvas, 67 * 82 cm| Marek Yanai

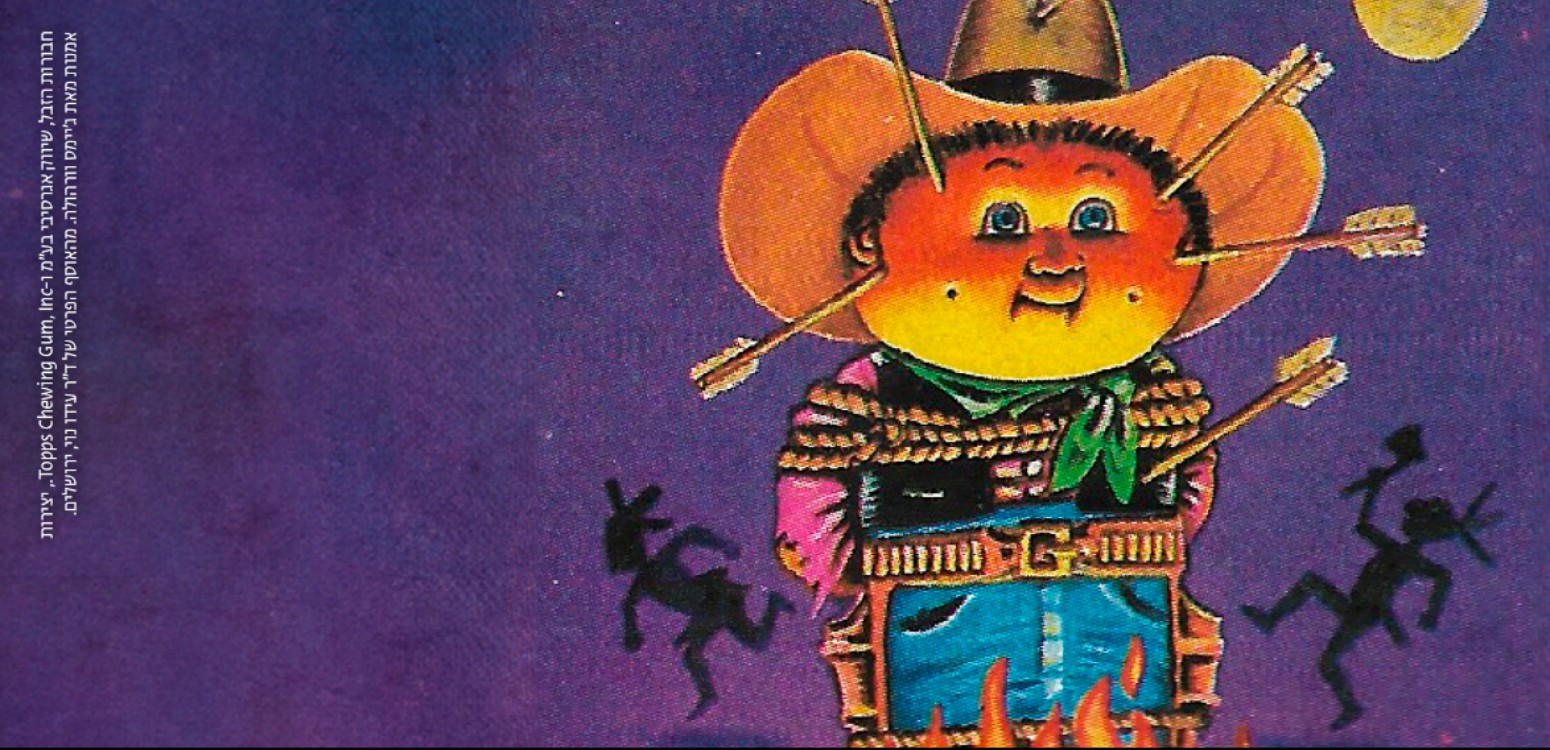

Breakfast in Katamon, Oil on Canvas, 65 * 65 cm|Marek Yanai

Meal for One, Oil on Canvas, 73 * 60 cm|Marek Yanai

Katamon. The Katamons. Secrecy endures inside houses, inside their rooms. Here, too, most spaces are devoid of people that nonetheless leave palpable traces: a carpet on the windowsill, bookcases, elegant living rooms, an unmade bed. Some works show tables set for a light meal, and it seems Yanai is emphasizing differences between neighborhoods through the food that is offered upon the tables. Meals are both cultural markers and status symbols, reflecting the ranks of diners in Jerusalem’s food chain.

An Israeli Breakfast, also known as “Breakfast in Talbiya” , is an ironic name given to the meal of newcomers or tourists from Anglo-Saxon countries: elegant dishes, a fine china milk jug, tea, quality sliced bread, an English edition of the newspaper Haaretz. The cityscape from the window is impressive, most likely a depiction of Old Katamon. A few hundred meters from there, “Breakfast in the Katamons” shows a completely different image of basic mass-produced food: a milk bag in a plastic pitcher, cereal in a cheap bowl. A blooming almond tree branch in a glass jar beautifies the scene in lieu of a window view. In “A Meal for One” (Page 43), the view from the window is dusky. On the table we see bread and a bottle of beer. We can imagine the painter, having worked all day, sitting down for his supper. Tomorrow he will return the key to the owners, who allowed him to reside briefly in their house and paint.

Abstract Nature, Oil on Canvas, 92 * 129 cm|Marek Yanai

Oil, water. On the Threshold opens with an unusual abstract oil painting from Yanai’s student years, reflecting Israeli art of that period. Yanai (very much like Avigdor Arikha) gave up abstract painting at an early stage, in favor of realism. But even in this early piece, the composition and use of color that would dominate his later works in oil and watercolors are already evident.

Over the years, Yanai painted only a few oils, each one was time consuming, produced using classic techniques, mainly focusing on views, openings, and still-lifes. But he Yanai frequently paints in watercolor, a technique that requires superb control while at the same time allowing one to let go. It’s a one-shot technique. The water drips, then spreads, becoming a spot or a line, continuing a dialogue with the white sheet of paper and the light, revealing images as it also blends into the colors.

Yanai’s mastery of watercolor is most purely expressed in his portraiture and paintings of trees. In one glimpse, he captures not only their physical attributes, but their nature, and aspects of their spiritual essence. Human heads fill the entire sheet of paper, seemingly floating, bodiless. Layers of watercolor reveal details that reality hides from our eyes. The artist paints professional models in his portraits. The sitters are all acquaintances, students, colleagues and strangers. Next to self-portraits and depictions of anonymous models, he has painted famous figures from the art and literary milieu: artist Danny Kafri (a fellow student from Bezalel), poet and artist Hedva Harechavi, literary scholar and translator David Weinfeld, and others.

Beit Avi Chai. This catalogue accompanies the On the Threshold exhibition – a selection of works from more than 50 years of artistic creation in Jerusalem by Marek Yanai. Encouraged by Beit Avi Chai CEO, Dr. David Rozenson, we allowed this exhibition to exceed the permanent gallery floor, so that for the first time we could display Yanai’s oil paintings separate from his watercolor, dedicate a room to his portraits, and show videos following his work process. The paintings are accompanied by poems by Jerusalem poets, creating a dialogue between various literary interpretations of reality and his works.

During the installation of this exhibition, my eyes wandered back and forth from Yanai’s depiction of the city center to the windows of Beit Avi Chai overlooking the same views, and for a moment I could not tell which was the window and which the painting.

[1] Amichai, Yehuda. The Poetry of Yehuda Amichai. Edited by Robert Alter. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2015